Video-Action Models: Are video model backbones the future of VLAs?

Elvis Nava

/

January 2026

This blog post is about mimic-video, our latest mimic release in which we instantiate a new class of Video-Action Models (VAM), grounding robotic policies in pretrained video models. We argue that video model backbones can be a much more natural choice for robotics foundation model pre-training compared to VLM backbones.

Do you want to work with us on this and more? We are actively hiring!

Preface

Vision-Language-Action Models (VLAs) have taken the robotics world by storm over the past two years. Even those of us who foresaw the potential of the “foundation model approach” to robotics likely didn’t foresee the speed at which these methods would be adopted by the robotics community.

Fundamentally, VLAs work as a general purpose solution to arbitrary robotic manipulation tasks, casting the problem of manipulation to one of freeform end-to-end pixel-to-action prediction, conditioned on language prompts. VLAs promise a future in which robotics can move away from task-specific bespoke engineering, towards general purpose tools that scale in performance with data and computation. They are the result of the robotics world finally taking Rich Sutton’s Bitter Lesson seriously.

This vision is powerful: having a robot perform an arbitrary manual labor task directly in the real world should no longer require a complex engineering project involving robot integration, programming, custom simulations et cetera. That whole workflow should instead be replaced by taking a pre-trained VLA, already generally capable for robot tasks, and fine-tuning it on task-specific demonstrations before directly deploying it on a robot system (and potentially running on-policy RL during deployment).

But how are current state of the art VLAs actually implemented? Models like pi0 and pi0.5, which came to be synonymous with VLAs, use a pre-trained Vision-Language Model (VLM) such as PaliGemma as a backbone, and on top of it train an action decoder on large scale robot action data. The VLM backbone comes pre-trained on internet-scale image and language data, which allows the VLA to generalize across language commands and ground its manipulation capabilities in a certain level of semantic understanding.

However, it does not seem obvious why a VLM would be the right choice of model backbone here [1]. The VLMs of today after all are pre-trained on a static image-language data mix that does not inherently favor knowledge of physical dynamics and motion, and is instead optimized for hill-climbing benchmarks like visual question answering. When training a robotics model on top of a VLM, all of the fine-grained understanding of physical interaction has to come from the expensive robot demonstration data, in the form of low-dimensional robot trajectories.

What should then be the right backbone for robotic foundation models? With our release of mimic-video, we argue that video model backbones pre-trained for video generation might be the answer.

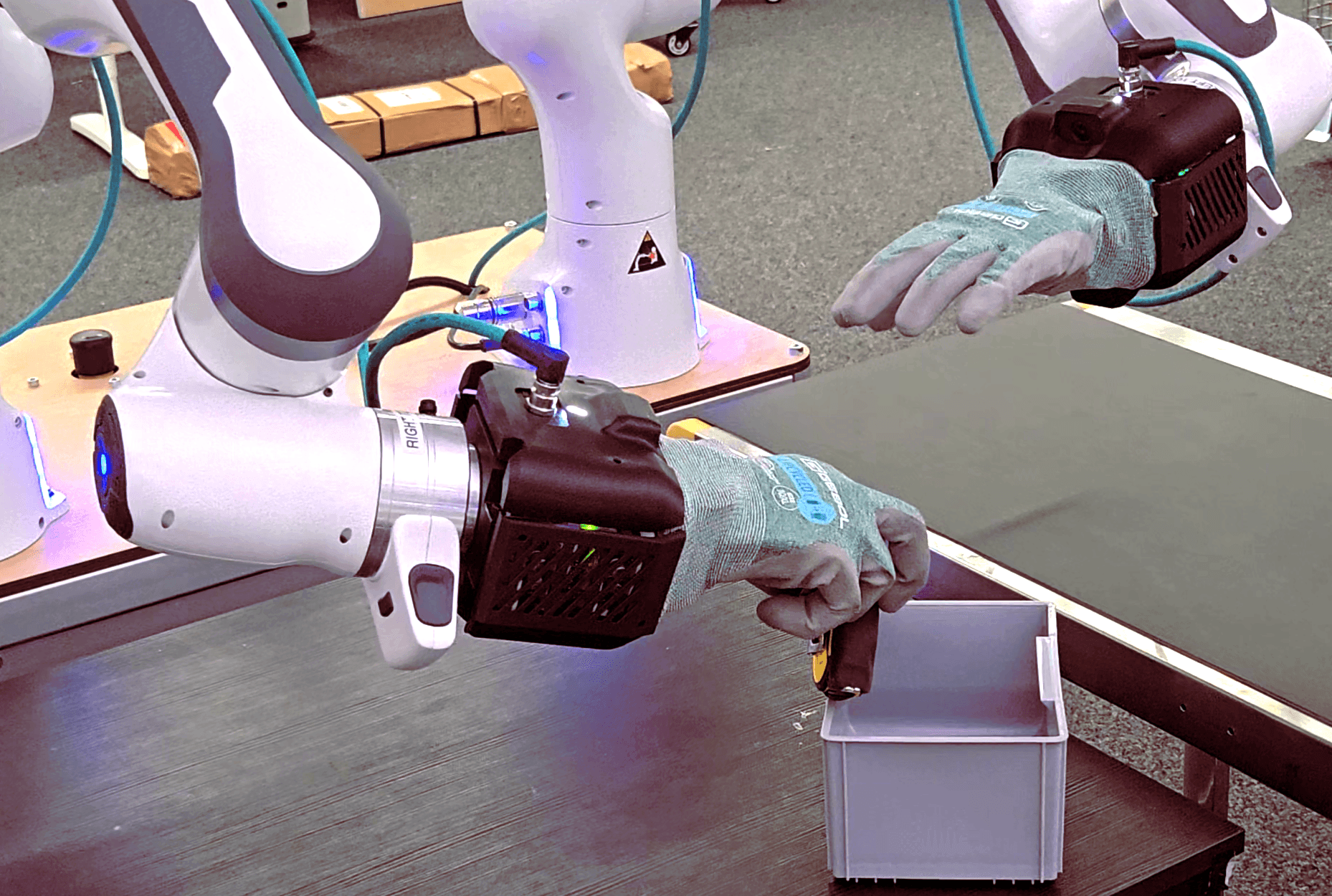

For each action chunk, mimic-video generates a latent video plan up to an intermediate noise level and then executes the actions on the real robot. We further fully denoise the predicted video for this visualization.

Video-Action Models: Why modeling video directly is the bitter-lesson way to go

Making use of large scale human video data for robot model pre-training has been one of mimic’s core propositions from the very beginning. Indeed, human video is the one “embodied action” data source that is already available at scale today, at quantities much larger than robot teleoperation data, and much closer to the data scales needed for comparable foundation model pre-training in other domains. However, up to now, nobody has convincingly demonstrated a simple, scalable recipe for making use of this video data for pre-training a robotics model in an unambiguously effective way.

Early attempts to do human video pre-training at mimic began from the common assumption that, in order for any useful action prediction model to be trained from large scale video, we would need to explicitly preprocess and extract low-dimensional actions from it. We soon found two big roadblocks:

Extracting low-dimensional trajectories from video is difficult, requires a substantial amount of engineering effort, and often results in low-quality, extremely noisy samples. Not only do several different processing steps need to be chained, we also need to sanity check and filter outputs without access to a ground truth.

There are many ways for low-dimensional action trajectories across multiple embodiments to be arbitrarily different from each other, despite the high-level behavior represented by the trajectories being similar. Data representation, format, capture frequency, preprocessing choices all contribute to these discrepancies, leading to data from one embodiment (such as human video) not being high quality or at all useful for downstream performance on another embodiment (such as a real robot).

All of this despite the intuition that such cross-embodiment data should be useful, especially given the common grounding of video [2].

If action extraction is so problematic, what is the solution? At some point in early 2025, our mimic-video lead authors Jonas Pai and Liam Achenbach decided to just scrap the whole preprocessing concept and take a bold shot at the rawest bitter-lesson brained approach they could think of.

Instead of taking a VLM backbone and specializing it for low-dimensional action prediction, mimic-video wholly replaces the VLM backbone with a video model backbone. We specifically chose Nvidia Cosmos-Predict2, a model for language-conditioned RGB video generation (sometimes referred to as a “world model”) pre-trained on large scale video data, including egocentric human and robot video, specialized for robotics applications.

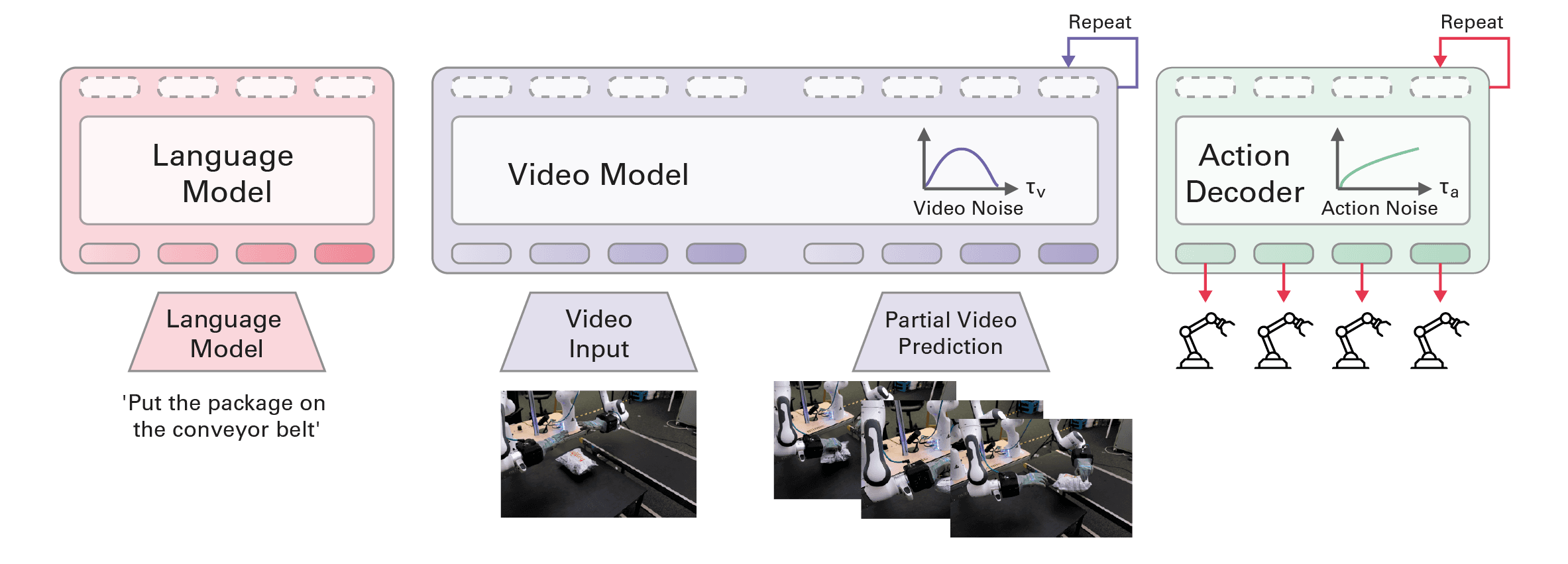

The mimic-video architecture replaces the VLM backbone with a video model backbone, pre-trained for video generation. The video model hidden representations are used to condition a small action decoder trained from scratch.

mimic-video instantiates a new class of Video-Action Model (VAM), a recipe that might hold the key to truly scalable robot foundation model pre-training. While VLMs are trained on static image-language data and have to infer most fine-grained behavior and dynamics information from the expensive (or hard to extract) low-dimensional action data, a video model can jointly model semantics, physical dynamics and high-level behavior in pre-training, without ever seeing low-dimensional robot action data. Only in a second phase, on top of this video backbone, do we train an action decoder, cross-attending to hidden representations from the backbone, similarly to what happens in a pi0.5-style VLA.

Intuitively, this approach makes a lot of sense. The state of the art of video models has recently advanced to the point of these models producing high resolution, coherent content involving realistic physics and human motion. Even the original Sora blog post framed the model as “a promising path towards building general purpose simulators of the physical world”. Social media short form content generation might have been an easy early avenue for monetization, but the ambition should be much greater: essentially, these models already “understand” how humanoid bodies should move in physical space to achieve arbitrary tasks.

We believe mimic-video to be one of the very first works showing how to straightforwardly go from this latent physical understanding to actual robot control.

Sample efficiency, convergence speed and inference

The need for expensive robot teleoperation data has often been deemed the bottleneck against true generative model scaling in robotics. If VAMs are the future of robot learning, we could blow past this roadblock: high quality RGB video of manipulation behaviors can be produced today by humans with no need for expensive robot deployments. Is this enough to unlock the era of scaling in robotics? If converting the video model into a robotics model can be done for cheap, then it might be.

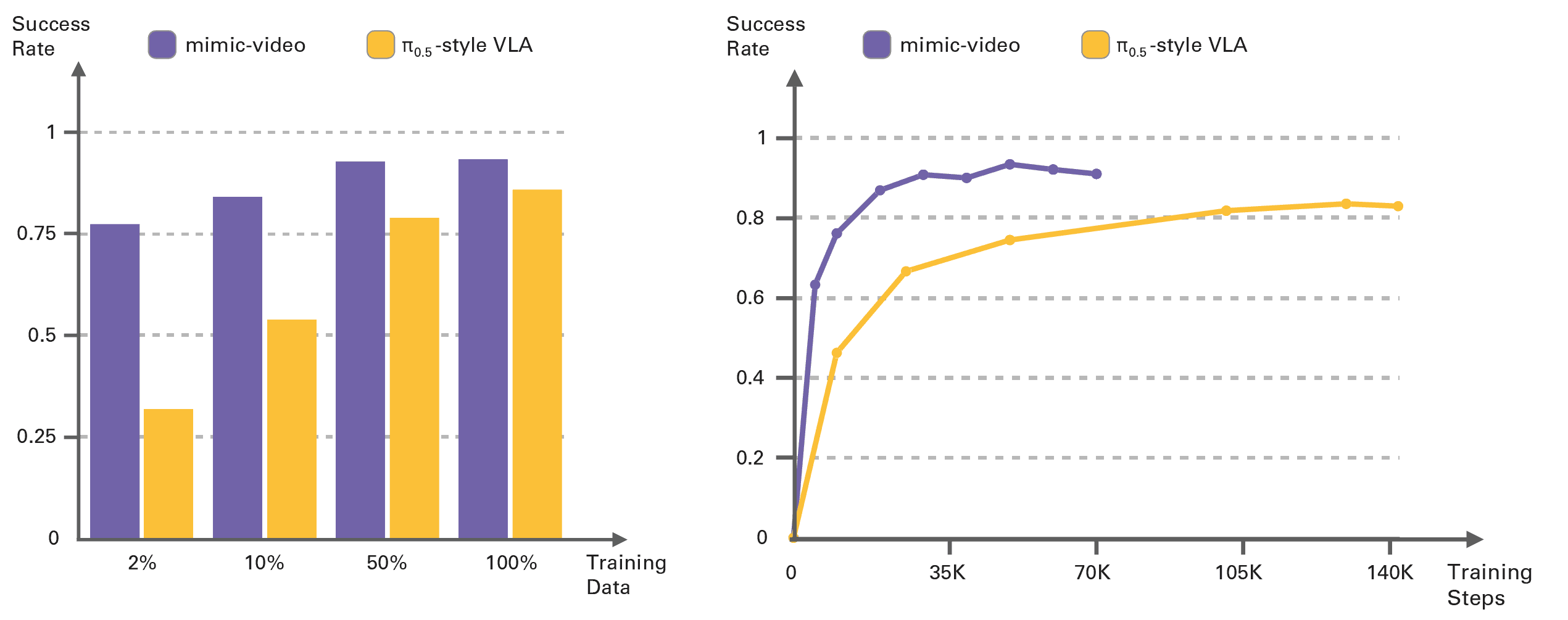

Indeed, what surprised us the most about mimic-video is just how sample efficient the action decoder training ended up being. We only needed to train the decoder on ~500 trajectories from our dexterous bimanual setup to achieve success rates only achievable with orders of magnitude more data with more traditional methods. On simulated benchmarks, we consistently observe 10x better sample efficiency and 2x faster action decoder training convergence compared to pi0.5-style VLAs. The takeaway is that future large scale robotics foundation models might be able to offload all planning to a video model backbone, while only needing a lightweight action decoder to translate these plans to low-dimensional actions.

Sample efficiency (left) and convergence speed (right) on the LIBERO benchmark. mimic-video achieves 10x better sample efficiency compared to a comparable traditional VLA. Decreasing the dataset size to only one episode per task (2% of action data) still yields a 77% success rate. Furthermore, mimic-video converges twice as fast as the VLA baseline, and to a higher asymptotic success rate, despite the VLA baseline having been exposed to task-specific action data during FAST-pretraining.

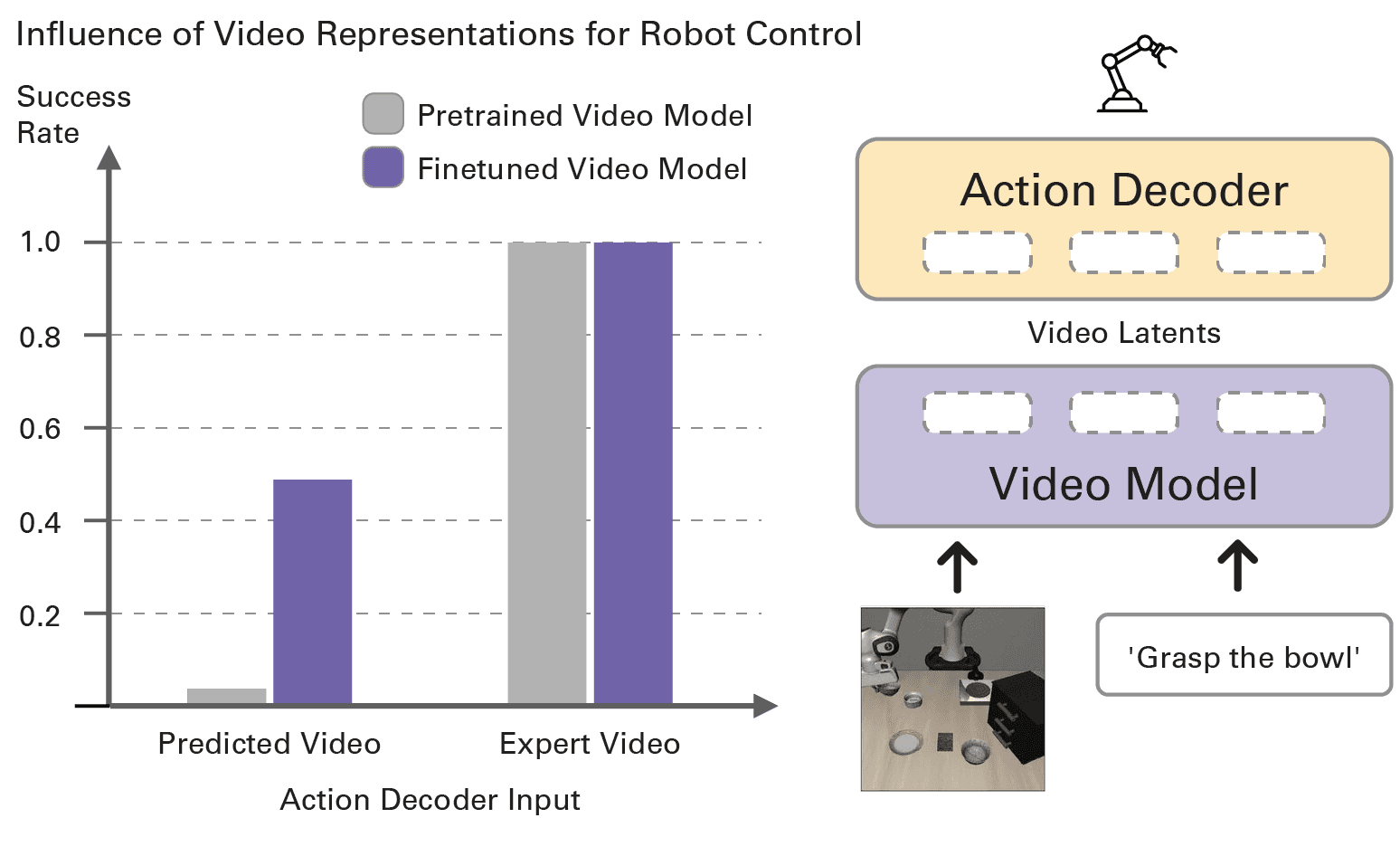

To further prove that the strength of robot action prediction in mimic-video is fully downstream of correct video prediction, we orchestrated an “oracle” experiment: giving ground truth future video as input to our video model backbone, we observed that the generated actions from the action decoder result in approximately perfect performance. Control effectively reduces to visual prediction, implying policy performance scales directly with the quality of video model predictions.

We compare success rates when conditioning our action decoder on different visual inputs: video latents generated by either predictions or ground-truth (expert) video for both features from a standard pretrained video model, as well as a video model finetuned on video data from the robot dataset.

The one remaining obstacle we expected to face was inference performance: even if our model attained all these benefits, wouldn’t video generation incur excessively high cost? It involves the arguably wasteful generation of visual embeddings, which have much higher dimensionality compared to the low dimensional robot trajectories that we ultimately care about.

Interestingly, we are able to bypass this problem by allowing for incomplete video denoising before action decoding. Not only are we able to run action inference after even just a single video backbone forward pass, proving that full video denoising is not needed: we also show that allowing for full video denoising is actually harmful! We have two main theories for why this is the case, from the fact that noisy video latents can act as an augmentation for the video conditioning signal for the action decoder, to considerations regarding the degeneration in the information content of hidden layer representations towards the end of the video denoising regime.

For more details, please check out the paper!

Why wasn’t this done before?

If video model backbones are such a no-brainer choice for robotics foundation models, why was the state of the art based on VLMs?

While it was only a matter of time until scalable, generative methods became the new state of the art in robotics, the type of pre-trained backbones these models would be based on was always going to be a function of what was popular, open source, relatively lightweight and easy to use, and VLMs like Paligemma perfectly fit the bill. It is only recently that we saw the release of video models like Nvidia Cosmos-Predict2, which is open weights, high quality and features a small 2B parameter checkpoint. The relatively small size of the video model was extremely important for us, as we wanted our experiments to both meaningfully make use of a pre-trained backbone, while at the same time allow for experimentation without the need for a hyperscale compute budget.

Moreover, the “obvious” use of a model like Cosmos-Predict2 in robotics was never initially going to be action generation, but rather use-cases purely requiring video generation, such as synthetic data generation or policy evaluation. While I do believe in the merits of world models for policy evaluation, I was always much more skeptical of using video models for synthetic data generation, beyond simple things like background or lighting augmentation. If a video model is good enough to generate useful data, why not just use its learned representations directly, instead of running what is essentially a difficult and error-prone policy distillation process on synthetic data?

Well, the answer is simply that the recipe for video model backbones in robot policy was elusive, up to now.

Conclusion

The implications of mimic-video could be transformative to the industry, as it is a recipe that promises to radically overhaul and simplify the pre-training data collection stack for robotics foundation models. There are however still many open questions, ranging from considerations of pre-training model training cost scaling, to the efficient support for multi-view robot policies.

But one thing is clear: the wild west of robotics most likely still hides several tricks for improving the Pareto frontier of robot model performance by orders of magnitude. We are all very early!

If you want to be amongst the early, you should join us.

References

Recent Twitter chatter agrees. ↩︎

Physical Intelligence recently published results alluding to preprocessed human data being useful for model fine-tuning, a capability emerging in models pre-trained with large scale robot teleoperation data. However, the results have only been shown to hold when the human data is used in fine-tuning, and the downstream performance improvements seem to mostly focus on simple tasks involving teaching the model novel task semantics with the human data, rather than complex motor skills. ↩︎